This article is for clinicians and prescribers of wheelchairs who may be working with individuals with Dementia. It is intended to raise awareness of the postural changes associated with the condition and provide solutions as to how we can respond with seating solutions for those in the more advanced stages of the condition when independent mobility is affected. Spex recently held a webinar “Immersed and Enveloped Positioning” in collaboration with Jo De Clercq, Physical Therapist, at De Wingerd Care Facility in Belgium (de Clerq & Churchill, 2021). The interest and feedback from that webinar was fantastic and highlights that this diagnosis warrants further understanding and focus for wheelchair and seating prescribers working with older adults and the various conditions with which dementia is associated.

What is Dementia?

When we think of ‘Dementia’ we may first think of memory loss as significant to impair daily functioning. It does, however, also present with physical changes that become more apparent as the condition progresses. Dementia affects people differently, results from a variety of diseases/injuries, and is caused by physical changes within the brain that affect the processing of information from sensory systems, musculoskeletal systems, and our environment by our cerebral cortex.

Types of dementia include:

- Alzheimer’s Dementia (most common)

- Lewy Body Dementia,

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease,

- Frontotemporal Dementia,

- Huntington’s Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson’s Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff’s Syndrome (alcohol-related brain damage)

- Dementia that develops following a stroke, with certain infections like HIV, repetitive physical injuries to the brain (chronic traumatic encephalopathy), or nutritional deficiencies (WHO, 2021).

Dementia is often considered a condition that affects older adults, but Alzheimer’s Research UK highlighted that there were, in fact, 42,000 people under the age of 65 with Dementia in the UK (Prince et al., 2014) and that the prevalence of dementia increases with age and over time – the numbers of people living with dementia globally is expected to increase from 50 million in 2018 to 152 million in 2050, a 204% increase (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia). Many of these individuals may end up living in care homes as they become more dependent on others due to cognitive and physical decline.

How Does Dementia Affect Posture?

We know that posture changes can happen as we age and with various diagnoses. Elderly clients are vulnerable to ill-fitting wheelchairs that are not comfortable, functional, or supportive. These wheelchairs may be standard manual attendant propelled solutions simply offered to help an individual access their social milieu and mobilise between locations, but without good contact between the body and supporting surfaces or without sufficient sensory feedback to provide information to the brain about how the body is positioned in space.

Individuals with Dementia will require a wheelchair as the condition progresses and the body’s ability to maintain posture and awareness of body position in space is affected. Wheelchair prescribers may not consider the brain’s inherent need for a more informed position to help ‘locate’ the body in space due to changes in the brain as this condition develops – failure to do this can result in increased postural distortions. To put this in very simple terms, consider how you might try to walk after suddenly developing a dead leg or developing pins and needles – your loss of sensory feedback to the brain makes it difficult for you to determine where your foot is in space and, as a result, you may trip or grab hold of nearby items for stability or present with an ‘awkward’ body posture of being more bent over to lower your centre of gravity or stabilise with your core muscles for added stability. What if you didn’t have any changes in sensation, but your brain now had difficulty perceiving where your body parts were in space? Another example shared by Jo de Clerq (de Clerq & Churchill, 2021) may be how we behave after visiting the dentist where we’ve had one half of our mouth and cheek numbed – we automatically try to find the ‘missing’ (sensory absent) part of our face by looking in mirrors, touching our cheeks with our hands or running our tongue along the inside of our cheeks to try to feel it.

Figure 1: Typical (fetal) posture of the patient with advanced paratonia with flexion and adduction of the extremities (Drenth et al, 2020)

Our postural management depends on the communication between our inner musculoskeletal system, our sensory systems, and the outer mantle of our cerebral cortex, combined with the environment in which we find ourselves. We know that providing reinforced support through walking aids, positioning systems when in bed, or seating systems when in a wheelchair can help individuals with musculoskeletal difficulties. We know that providing good contact between the body and its supporting surfaces can help distribute pressure and can also provide sensory feedback to the brain and musculoskeletal system to inform the brain as to the body’s position in space.

Postural stability is affected by the demands on our cognitive system. Mesbah et al. (2016) found that postural stability in older adults was reduced when visual input was reduced or when individuals needed to concentrate on multiple tasks. Individuals with Dementia will experience motor abnormality known as paratonia – in an article by Drenth et al. (2020) they identified that this is not well understood, however, motor decline is associated with cognitive decline and, therefore, this will affect wheelchair prescriber’s ability to optimise seating systems for these individuals as cognition, and mobility deteriorates and dependency increases.

Paratonia is “a form of hypertonia with an involuntary variable resistance during passive movement. The nature of paratonia may change with the progression of the dementing illness (e.g., active assistance) is more common early in the course of degenerative dementias, whilst active resistance is more common later in the course of the disease). The degree of resistance varies depending on the speed of movement (e.g., low resistance to slow movement and high resistance to fast movement). The degree of paratonia is proportional to the amount of force applied. Paratonia increases with the progression of dementia. Furthermore, the resistance to passive movement is in any direction and there is no clasp-knife phenomenon”.

(Hobbelen, et al., 2006)

Paratonia may present in 5% of individuals with mild cognitive impairment and 100% of individuals with Dementia (Vahia et al., 2007; Hobbelen et al., 2010), with this becoming accelerated as the central nervous system becomes more affected (Drenth et al., 2017) and may serve as a physiological and psychological stabilizing mechanism (Souren et al., 1997) or to serve as a mechanism to gain additional tactile sensory information due to the loss of proprioception (van der Rakt, 2007). Again, think of how much you might move your jaw or lips after visiting the dentist!

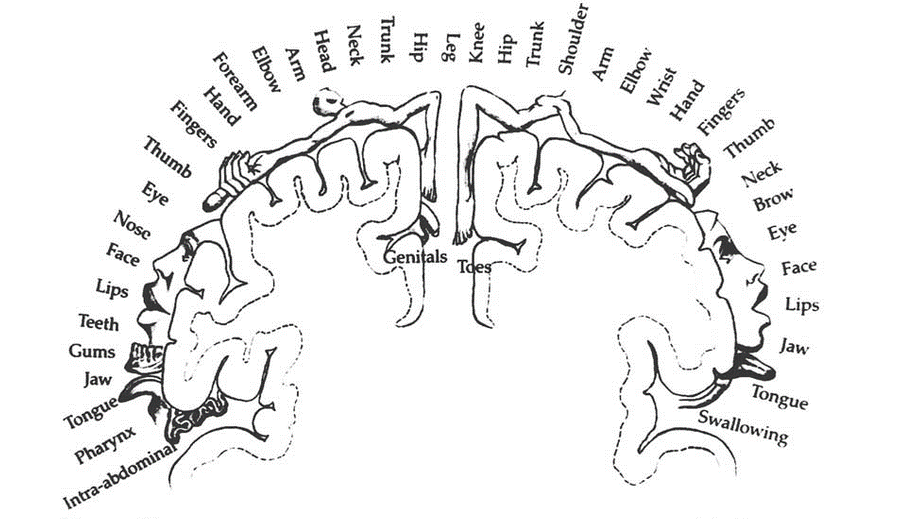

Postural management can be affected by how the brain pathology affects the cerebral cortex including areas like the somatic sensory cortex, motor cortex, and the insular cortex within the brain. These are some areas that deal with information arriving in the brain (sensory information) and how our bodies then respond to this information (motor response). Although dementia is a diagnosis that almost everyone has heard of, many may not fully understand how it impacts the body’s postural management system. The seating system can provide sensory feedback to the brain to inform the sense of body position in space – it can offer this through immersion and envelopment.

The progression of mobility changes in dementia can be summarised by five stages (ARJO, 2019) with the final three stages anticipating the motor changes that will lead to wheelchair use as the cognitive changes occur. (De Clercq, 2021) Persons with Dementia in the 3rd stage may start requiring a wheelchair for mobility. In the 4th and 5th stages, the person will be dependent on a wheelchair and/or bed and require an increased need for support. The wheelchair will need to adjust to changing from a self-propelled wheelchair in the 3rd stage to a more supportive and potentially attendant propelled solution with increased support around the body, limbs, and head. The seating system must be able to adjust to changing needs as the condition progresses and sensory feedback requires additional seating configuration needs to provide stability.

Figure 2: Mobility GalleryTM (ARJO, 2019, p.12)

Why Do We Need Immersion and Envelopment Within Seating Solutions for Persons With Dementia?

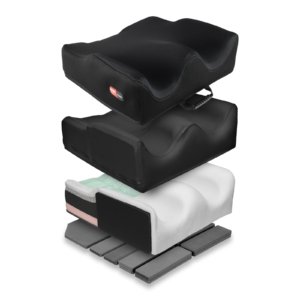

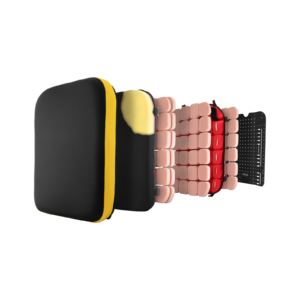

Immersion can be defined as the depth to which a body will penetrate the supporting surface, whilst envelopment is the extent to which the supporting surface conforms to the body shape as it immerses. These two factors are recognised as key characteristics to improve pressure distribution and reduce the risk of pressure injuries (Morello et al., 2020). These two characteristics also allow the body to relax into the materials of the seating system for optimisation of contact to areas that need support. Seating systems can be created using various materials and these materials have varying abilities to facilitate this. If these two characteristics are met but are not able to allow off-loading (the ability to move pressure from one part of the body to another) to reduce pressure, then there is still a risk of pressure injury formation.

Various research highlights that the brain shape and density can change with dementia. This can mean disruption to the neural pathways that allow our brains to respond to sensory information, process this information and adjust our posture and movement in response. There is still much to learn about the brain, however, our seating system needs to optimise every opportunity to inform the body senses of the support available to reduce paratonia and allow the wheelchair user with dementia to accept the base of support and feel supported. We need seating solutions to offer as much information and stability as possible to reduce emotional and motor responses that may result in postural deviations. (Berrett et al, 2019; Carmichael et al., 2007; Uddin et al., 2017)

Essentially, we can use the seating system to create a ‘hug’ that allows the body to be well supported and cocooned by the cushion, back support, lateral supports, and head support. We can use materials that conform to body shape, mould around the body to envelop and cradle weight-bearing segments (head, trunk, legs, pelvis, arms) and we can use modular systems that allow for improved contouring that can adjust over time to changes in body shape as the condition progresses.

How Can a Seating System Provide Sensory Feedback as well as Reinforced Support?

When we consider sensory processing in the brain we may focus on sensations of the eyes, mouth, face, hands, feet – these are the body parts that interact and process information from our environment the most and which we may be most aware of. But we cannot forget about the parts of the body that interact with our supporting surfaces when standing, lying, or sitting (think the bottom of the feet, back of the head, the back, under your forearms or upper arms, back of the trunk, buttocks, bottom of the feet, back of our thighs). What we feel can influence how we move or hold ourselves (see Figure 3 below).

It is important that we optimise this contact for individuals who have impaired proprioceptive and sensory processing due to dementia. It is also important that these surfaces contour to the body for optimum contact to create a ‘hug’ that provides sensory feedback and stability without creating any pressure points. We still need to optimise the body against gravity in sitting and must also consider the lateral trunk supports that provide reinforced support and sensory feedback to the trunk.

| The Motor and Sensory Areas of the Cerebral Cortex | |

|

|

| Somatic Sensory Cortex | Motor Cortex |

Figure 3 Original illustration of the sensory homunculus by Wilder Penfield

(https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253614317)

The Spex modular system uses various foam densities to provide immersion and conformity within the cushions, back supports and head supports. The cushions and back supports include a pocket layer system that allows additional foam supports to be added or removed to respond to pressure needs, conform to body shape to optimise contact, and allow immersion and envelopment into the supporting surfaces.

This added shaping allows the wheelchair system to accommodate or reduce postural deviations that may present, such as kyphosis. This added shaping can also create a ‘hug’ around the underside of the pelvis and legs, and around the wheelchair user’s back, whilst simultaneously providing reinforced support against gravity and sensory feedback to help provide an informed and stable sitting position. Lateral trunk supports provide additional support and sensory feedback to the trunk without compromising the movement of the arms. The head support cradles the occiput and back of the head without restricting side movement, reducing the effort to hold the head up against gravity and providing sensory feedback.

So, What Do You Need to Consider in a Seating System for Individuals With Dementia?

A wheelchair is often not considered or required in the early stages of the condition but may be required in the more advanced stages when body systems are more affected and muscle control for mobility deteriorates. It may initially be to support an individual to access community environments where the sensory demands are higher and may be required for indoor use also to support engagement in social activities, eating, and leisure activities. A wheelchair can facilitate participation to maintain socialisation and improved quality of life and needs to be able to respond appropriately to postural distortions linked to reduced body scheme awareness and spatial awareness to maintain comfort and engagement.

We need the seating system to provide key elements such as:

- Providing appropriate pressure relief

- Providing support and positioning to minimise fatigue

- Facilitate engagement in functional activities and promote independence, including propelling the wheelchair, accessing transport and the wider community

- Supporting the body to maintain a healthy alignment against gravity at the hips, trunk, and head

- Optimise posture for cardiac, respiratory, and gastrointestinal functions.

- Allow for independent and assisted transfers, as appropriate.

- Be aesthetically pleasing and allow for self-expression

- Adequate support to the pelvis and trunk to provide stability

- Adequate support to the arms and head for higher-level injuries

- Protection of body parts with limited sensory feedback

- Be easy to use by client and family/carers

- Provide comfort

This is, in fact, no different from general characteristics that any wheelchair should provide but prescribers will need a greater understanding of the sensory processing system changes and how a seating system will need to offer immersion and envelopment to inform body position.

Finding seating systems that offer optimal contact and conformity to body shape, whilst also allowing responsiveness to changing needs relating to immersion and envelopment (to provide proprioceptive feedback to inform the brain of the body positioning in space), may not be considered or readily available in the later stages of dementia. We know that the lying position informs the sitting position – our position we adopt in lying will affect our posture in sitting – and therefore wheelchair may need to respond to an increasing foetal position mirrored in sitting. For this reason, the importance of 24-hour posture management cannot be overemphasised – providing an informed lying position is vital where the lying position allows for an informed body position to reduce motor abnormalities associated with the condition as it will positively influence seating position. And whilst the seating position remains tolerable, the seating system, too, must provide stable support that provides an informed body positioning sense to the individual.

Assistive technology considered for this diagnosis tends to focus on memory impairments, visual impairments, or smart technology to optimise independence within the home. A wheelchair is also assistive technology. Assistive technology can improve participation in daily living, socialising, safety, and engaging in leisure activities. A wheelchair can facilitate this and can also optimise engagement and participation in the later stages of the condition.

How Can Spex Respond to Meet the Clinical Seating Needs of Persons with Dementia?

Spex recently had the privilege of hosting a webinar with Jo de Clercq, Physiotherapist at De Wingerd Care Facility in Belgium. Jo has been using a Spex system with one of his clients with advanced dementia and reported that by providing immersed and enveloped positioning with the Spex modular products, he was able to provide enough body positioning sense and stability for his client to resume eating finger foods after previously being fully dependent during mealtimes. The dementia had not reduced, but the way that the seating system was able to provide sufficient stability, comfort, and sensory information to the body enabled the wheelchair user to regain use of his arms to interact with his environment and improve his quality of life.

This system allowed adjustment to meet postural needs but adding shaping and contouring and therefore allowed:

- Optimal contact between the supporting surfaces and the body – footrests, cushion, back support, head support, arm support.

- Immersion into the supporting surface to provide sensory feedback and stability.

- Envelopment of the supporting surfaces to the body shape contours for pressure distribution and comfort.

Education is for improving the lives of others and for leaving your community and world better than you found it.

– Marian Wright Edelman

Thank you for reading. If you have any thoughts or questions, please leave them below.

If you would like to learn more about how Spex can respond to the needs of this client group to optimise quality of life through informed and stable positioning, please contact the Spex Clinical Educator Team to arrange additional training.