This clinical resource will discuss some of the differences between bariatric and non-bariatric populations and key considerations in providing seating solutions for this wheelchair user cohort. It is important to understand this because failure to match technology to the person’s needs can result in adverse consequences relating to pressure management, postural support, and/or comfort. Body shapes can be so different and seating solutions need to respond accordingly. Obesity is on the rise – “In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight. Of these over 650 million were obese.” (WHO, 2021) Obesity can be a consequence of injury or illness, such as enforced periods of inactivity or bed rest after illness or injury or, for example, conditions where cardiovascular, lymphatic, and/or endocrine functioning may be compromised.

What is ‘obesity’?

“Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health. A body mass index (BMI) over 25 is considered overweight, and over 30 is obese. The issue has grown to epidemic proportions, with over 4 million people dying each year as a result of being overweight or obese in 2017 according to the global burden of disease.” (WHO, n.d.)

Using the Body Mass Index scale scores of mass divided by height as a guide (kg / (m)2), any result over 25 indicates being overweight, obese (30-39), or morbidly obese (40 or more). This guide is not always a very clear indication of the percentage of body fat – consider, for example, a very muscular athlete may show as having a high BMI but have less body fat. BMI, height and weight are still measurements that allow seating specialists to consider additional factors that have to be taken into account when prescribing assistive technology and equipment.

It is important to note that a stigma around obesity exists. Obesity can be a result, a secondary consequence of an illness/injury (physical or psychological), which in turn, further adversely affects general health and co-morbidities.

What must we think of in relation to equipment?

All products have safe working loads which maintain the working integrity of the materials and structures within them when moving and handling or supporting. Different types of materials also offer better responsiveness relevant to the purpose/function they need to support. Failure to heed these can lead to product failure, sometimes with disastrous consequences to the load (person) being transported or supported.

A very simple example I have relates to my shoes. I have some shoes that respond beautifully to all-day wear and comfort because of how the soles are manufactured and how the feet are cushioned within them during prolonged standing. I have other shoes more suited to running, but not necessarily very effective for standing for long periods. I have slippers that are perfect for providing warmth, but ridiculous at providing any significant foot or ankle support. Wearing these shoes for the wrong purpose can lead to blisters, leg and back pain, and increased wear and tear in the shoes. Shoes may have poor load-bearing capacity, wearing can be time-limited for comfort and design can affect functionality and ease of use. This is the same for cushions used in wheelchairs.

Seating solutions in wheelchairs need to be fit for purpose when considering body shape, person load (weight), functional use, and skin integrity. Wheelchair cushion materials have safe working load limits. Exceeding these limits is a lot like trying to stand for a long period of time in high-heeled shoes – it will cause pain and discomfort and possible skin damage. Different material configuration is needed to ensure that the correct support is offered for greater weight responsiveness. We cannot ignore the health impacts that the person’s medical presentation has on the body – there may be a sensory loss, reduced oxygen perfusion in the tissues and, even, increased perspiration; the person factors need to be matched with appropriate materials to reduce the risk of skin breakdown, poor thermoregulation or further compromised respiration due to ineffective postural support.

Another key consideration is whether the seating system can respond to particular body shapes. Increased weight may manifest differently on the body (Dionne, 2006) – this can be around the legs and hips (pear-shaped) or around the abdomen (apple-shaped). These presentations can mean a wheelchair and seating system needs to respond to different key measurements between the upper and lower body. Seating systems should not only respond to the soft tissue changes of a person with size but should also allow for clinical responsiveness to postural asymmetry (lordosis, kyphosis, scoliosis, hip flexion asymmetry).

To summarise this section, wheelchair equipment needs to respond to the outer body shape of a person with size, but it also needs to respond to the postural asymmetry needs, which may be less apparent. Key considerations include:

- Seat width vs trunk width

- Seat depth (this may be compromised if needing to accommodate larger calves)

- Seat height – mobility may be further compromised for a person with size therefore seat contouring and seat height may adversely affect transferability if not assessed.

- Soft tissue accommodation around the trunk, pelvis, thighs, trunk, and calves.

- Back Support contouring – a planar (flat) option may be appropriate, although it is likely that contouring around the lower back or trunk may be required to respond to body shape and postural asymmetry.

- Responsiveness and placement of lateral trunk supports

- Integrity and configuration of cushion and back support foams to provide sufficient support, immersion, and envelopment. Be aware of potential increased shear forces.

- Safe load bearing of hardware and seat base or back support mounting

- Head Support position and allowable adjustments to respond to body shape and postural asymmetry.

- Stability to the body without compromising body shape yet optimising contact for pressure distribution.

- Thermoregulation qualities of the products that can aid with moisture wicking

- Overall weight of the wheelchair and how this may affect self-propelling ability or the ability of another to push the wheelchair.

- Stability of the wheelchair if an individual’s posterior pelvic tissue distribution or presence of a panniculus (hanging flap of tissue involving the abdomen and can include parts of the abdominal cavity if part of a hernia) results in pelvis sitting forward on the seat anterior to the rear wheel axis of the wheelchair chassis.

What Must We Think of in Relation to the Person?

I believe many more people of size fight for independence that the media portrays.

[ ] We need to bring the individual patients back into the focus.

(Dionne, 2006, p. 9)

Postural responsiveness of a wheelchair and its seating system needs to be considered for a person of any size. As should whether a product meets clinical and function needs and the potential to future-proof products so that they adapt as the user’s body shape, also, may adapt and change.

As mentioned previously, obesity can be a secondary condition with the causative diagnosis/condition impacts on cardiovascular function, mobility, and/or cardiopulmonary function. Regardless of the presence of obesity, we need to focus on the postural need, functional goals, and quality of life. A good understanding of biomechanics is needed, and a thorough assessment is essential. The assessment should include:

- Functional goals

- Environment – where is the equipment is to be used and for how long

- Personal history:

- Weight history (loss/gain/unstable/stable)

- Height

- Medical condition(s)

- Upper limb and cardiac/respiratory function (especially if self-propulsion is considered)

- Pain

- Skin integrity

- Communication needs

- Mobility:

- Arm function

- Leg function and transferability

- Range of movement

- Muscle tone fluctuations or changes

- How the tissue distribution affects seated posture (Tanguay, 2018)

- Increased abdominal tissue distribution can place pressure on the thighs leading to hip abduction;

- The presence of a gluteal shelf (posterior pelvic tissue distribution) may require back support to be able to come forward to meet the trunk whilst accommodating this tissue distribution;

- The presence of the gluteal shelf could potentially affect the alignment of ichial tuberosities in the ischial well if not taken into consideration; and

- Increase pelvic and femoral tissue distribution may require wider cushion width compared to back support width.

- Key body measurements

- Tanguay (2018, Fig. 19-5 & 19-23) identifies key additional measurement considerations are required for persons of size. These include:

- Width across the toes/widest part of the calves/widest part of the thighs/lateral elbow to elbow (outer aspect)/back of head to scapula depth difference.

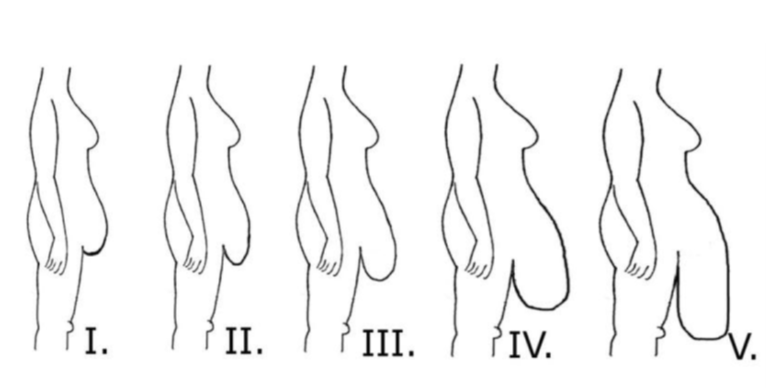

- Pannus (panniculus) measurements that must be considered for influence on sitting posture and potential wheelchair cushion and seat pan customisation as this will require additional seating configurations to allow for comfort and stability in the chair. This may also affect the ability for the user to move back on the seat and lead to wheelchair instability or increased front loading through the front castors. The pannus is likely to increase hip abduction when sitting and move centre of mass anterior – see Fig 1 below (Hillenbrand, 2012)

- Tanguay (2018, Fig. 19-5 & 19-23) identifies key additional measurement considerations are required for persons of size. These include:

- Wheelchair frame measurements:

- The height of the lower aspect of the back support (this may need to be above the gluteal shelf and have hardware that allows the back support to be positioned forward of the wheelchair canes with adequate space to fix back support hardware; and

- The presence of a back bracing bar, if present, may compromise planned back support recline angle changes, if required.

- The position of the head support – this may fall further anterior compared to the position of the scapula and therefore require extension hardware to allow the head support to meet the back of the head

- The foot supports may need to accommodate additional width across the toes (lateral aspect) and the foot support hangers should not be causing any discomfort by pressing into the lateral aspect of the lower legs.

- Arm supports should support the arm without impinging on the abdominal or pelvic tissue.

How can Spex support people of size?

Spex has just launched their new product range for people of size. It provides standard contour cushion and planar options (XLella Vigour) as well as the contourable cushion and back support options (XLella Spex cushion range with varying contours), with an added responsiveness for accommodating the posterior pelvic tissue distribution with the XLella Adapta2. You can find out more about these solutions by ckicking the link below.

Spex XLella Bariatric Seating Range

Customisations within these products specific to this user cohort are available – please discuss with your local Spex supplier in the first instance.

Spex lateral contouring and stability solutions by way of the lateral trunk supports are fully compatible with these new backs. A consideration for use with a person of size is to include the reinforcement plate to provide additional load-bearing capacity (pictured right).

If you have faced any particular challenges with providing posturally and clinically responsive solutions for this particular wheelchair user cohort, or have questions about how Spex can support you with your personal seating, please comment below or contact us via email.

Thank you for reading!

- Hillenbrand, A., Henne-Bruns, D., & Wolf, A. M. (2012). Panniculus, giant hernias and surgical problems in patients with morbid obesity. GMS Interdisciplinary Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery DGPW 2012, 1. Retrieved 18 January 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Panniculus-classification-according-to-Igwe-Jr-et-al_fig1_285620672

- Igwe, D., Stanczyk, M., Tambi, J., Fobi, M., Lee, H., & Felahy, B. (2000). Panniculectomy Adjuvant to Obesity Surgery. Obesity Surgery, 10(6), 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089200321593742

- Obesity. (n.d.). Retrieved 18 January 2022, from https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/obesity

- Obesity and overweight. (2021, June 9). World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Tanguay, S. (2018). Chapter 19: Considerations when working with the bariatric population. In M. L. Lange & J. L. Minkel, Seating and Wheeled Mobility: A clinical resource guide (pp. 317–332). Slack Incorporated.